Walk with Me (dir. Heidi Levitt)

Heidi Levitt is a familiar name in the credits of Hollywood productions, although you may not have noticed. She’s worked as a casting director on films by Oliver Stone, Wayne Wang, Adrian Lyne, Wim Wenders and Michael Bay, casting American presidents, groundbreaking ensembles, and big budget action spectacles as well as a raft of independent and low budget features. This year’s introduction of a casting Oscar is long overdue and it’s hard to imagine she wouldn’t have been at the very least nominated once (JFK) or twice (The Artist) if they’d figured it out earlier.

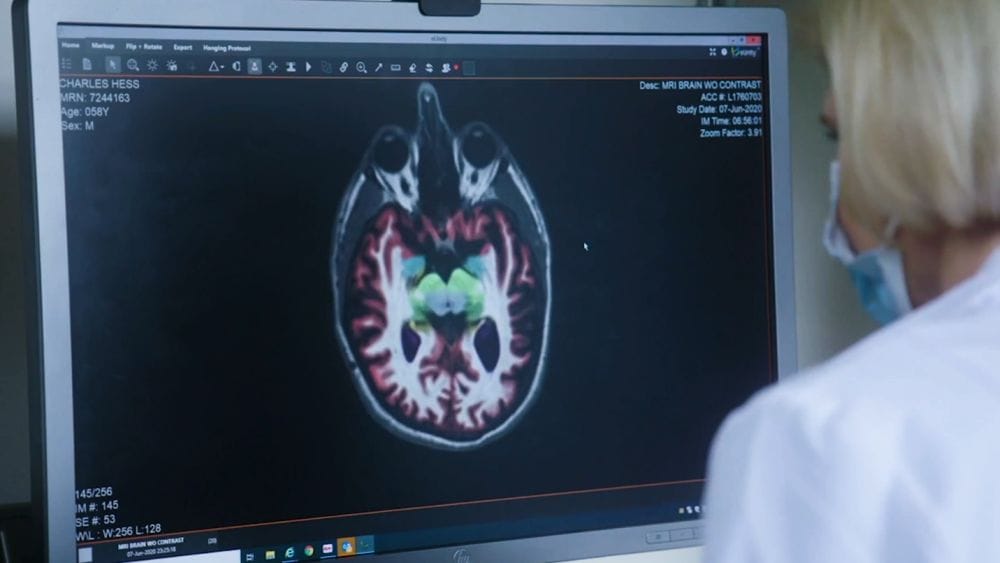

It feels noteworthy to mention this because we rarely learn too much about casting directors. Beyond the stories in, say, Tom Donahue’s Casting By, casting directors aren't often the focus of stories, interviews or panel discussions that come with the award season nonsense. They are largely anonymous to most filmgoers even if they are as important as anybody else. It's hard to imagine a movie like Walk with Me without that anonymity. This is, after all, a film that goes into the life of Levitt and her family with some confrontational candour. Here, Levitt not only picks up the camera herself for the first time, but she attunes it to herself as well. Herself and her husband, Charlie Hess, who has been diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease.

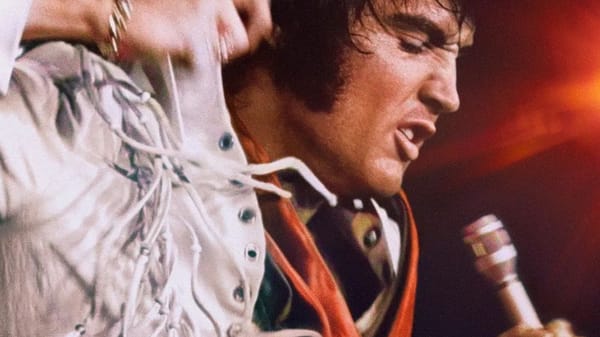

Whether it's through personal experience or through film, television and literature, we all unfortunately know what this debilitating illness can do the human body. At the film’s start, Charlie is 57-years-old and is already experiencing those cognitive declines. He has been forced to leave his career as a print magazine art director and graphic designer, he experiences confusion and the loss of language, he has outbursts of anger at his wife as his personality changes through no fault of his own. We watch him at doctor’s appointments, somewhat accepting of the medical verdict he is facing—perhaps stubbornly so. We observe how he adapts as a creative person to a disease that has stripped him of his abilities as well as often stripped him of the personality that his creativity stemmed from in the first place.

We also see Levitt herself taking on the role of caregiver. She is not just the second half to this marriage, but the second half to Walk with Me’s narrative as Heidi sets out to do what she can for the man she married and the father of her children. She attends meetings with doctors alone and with Charlie. “You know that caregivers die at a rate 63% higher than their same age group,” says one doctor with whom the first-time filmmaker consults. It’s an alarming statistic that is sadly not surprising in the slightest and it frames Heidi and Charlie’s stories in a way that allows its story to linger long after the credits. For the story of Walk with Me doesn’t end when the credits roll. And that’s one of the great assets of Levitt’s documentary, the understanding that this film cannot tell the entire story of this couple, nor the story of anybody else with Alzheimer's Disease, either. But Levitt’s work here is sharp, bringing clarity to both sides of the diagnosis. In that regard, it is similar to Ondi Timoner’s Last Flight Home about a family member’s assisted dying. Or even Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland narrative feature Still Alice, which at the time of its release in 2014 was too often dismissed as “a Lifetime movie” but which with every passing year looks more and more mature and graceful in its telling of a story very similar to that of Walk with Me.

Levitt with her editor Simeon Hutner and supervising editor Toby Shimin weaves her family’s contemporary journey with beautiful, fluttering home movies. Not just filling in details of their life before Alzheimer’s for the audience or even for her own children, but also offering Charlie a gateway into the memories he is rapidly losing. While the otherwise standard digital photography is devoid of cinematic tricks, Levitt shows a lovely knack for the storytelling craft. She leaves the camera rolling through difficult, personally traumatic sequences and doesn't cut away from the moments that are difficult to watch.

Despite its subject matter, Walk with Me isn’t too dour of a experience to endure. It’s sad, yes; of course it is. But the autobiographical nature of its storytelling allows for much more unfiltered tenderness than one might expect. It taps into something that an outsider may not have been able to navigate quite as well. When she captures her son, Tobias, making a stark realisation about his father (within the experience of being a young twentysomething with an all-too-suddenly ailing dad), it’s the sort of thing that might not have been able to occur without Levitt’s steady hand as a filmmaker. She knows when to end it, too, having told just enough of the story to be helpful and not so much that it impacts her subject. This is an illuminating film from multiple angles, sharing the desperation and the bonds that are fortified in such instances.

If you would like to support documentary and non-fiction film criticism, please consider donating by clicking the above link. Any help allows me to continue to do this, supports independent writing that is free of Artificial Intelligence, and is done purely for the love of it.