Sydney Film Festival – Gods of Stone (dir. Iván Castiñeiras)

There was a moment around midway through Iván Castiñeiras’ Gods of Stone (Deuses de pedra) film where I thought to myself, ‘You can really tell this was shot over 15 years’. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing, although I think in the case of this 80-minute film, it does somewhat have an effect on the rhythms of rural life that Castiñeiras captures so well. It is a documentary that starts maybe as something a little big shaggy in its structure (despite that lean runtime), focused on sights and sounds and curious little diversions from his decade-plus filming, that then shifts to something slightly more manicured with its gaze shifting primarily to that of one young girl’s quandry about staying in her hometown village or leaving for the bigger city. I think I wanted one or the other, but assembled as it is gives Castiñeiras’ debut feature a slight uncertainty that I don't think was entirely successful.

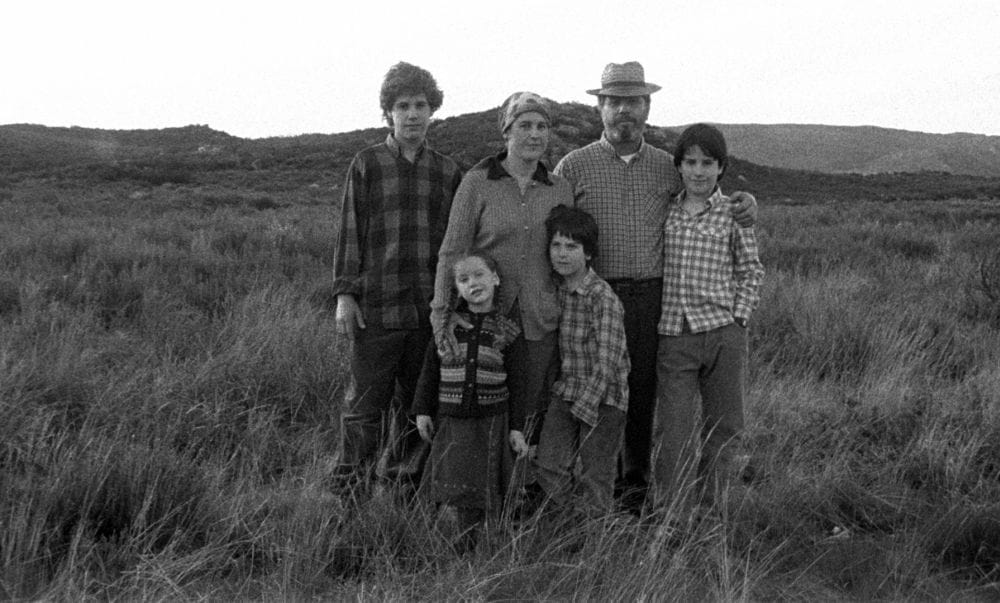

Gods of Stone is a story of fragments. Shot in 16mm initially in black and white before quickly shifting to colour, it is vibrant to look at, full of lush countryside colours. All greens and browns and blues. Castiñeiras’ own cinematography captures the experience of this life growing up on the border of Spain and Portugal gloriously. The use of analogue film works not just to capture its beauty as elegantly as possible, but to evoke a time and place of Castiñeiras’ own childhood. It isn’t nostalgia so much as it is the way an artist’s mind may remember their youth, shot and assembled in his mind like a movie. These early passages were my favourites, all sows and bulls and foraging soundtracked largely by chimes and nature and local musical instruments. Early on, we hear from adults who have returned to the region because of its quality of life, which sparks an ongoing theme throughout the rest of the movie around this idea of rural living. How sustainable is it for the youth of today who have smart phones and all-too-easily see a more exciting life for themselves where once it may have been just the concept of an idea. And while we don’t necessarily see much of it here, these themes naturally conjure up images of simple farming villages being turned into tourist towns for city folk to get their fill of country life and how that can alter once more the makeup of their inhabitants' lives.

Later scenes focus more closely on Mariana Freitas Tavares, the daughter of divorced parents whose eldest brother has already moved away and is now reeling from the (inevitable, one has to assume) revelation that her other brother is also planning to leave. Where does that leave her, a young woman who doesn’t quite share the same dreams of the big city like her brothers and classmates. We don’t get into that too much, which is a shame but a natural symptom of Castiñeiras’ observational approach so it's hard to be too upset. She says (with some minor hesitation) to her friend that she'd like to return after university. But the question begs to be asked of how she can survive there if everybody else is leaving. And for that matter, how can towns like hers survive? A brief suggestion to the opening of a lithium mine making this town uninhabitable is strangely left unexplored despite seeming like quite an important element of this town’s story.

This sort of Boyhood-esque approach to filmmaking actually really suits Mariana’s story, but Gods of Stone’s earlier passages are not as keenly focused on her, which makes the film somewhat lopsided. Especially since these later portions have something of a scripted quality to them that struck me as counterproductive to the collage like style of its first half.

Still, editor Antonio Trullén Funcia does fine work in attempting to tie together 15 years worth of content. I particularly enjoyed the way he incorporated symmetries throughout—a woman kneads bread one moment before cutting away to her scrubbing laundry on a rock in the next, processes made of similar motions; girls playing tag as children before many years later playing once again as teenagers; girls performing a choreographed dance routine on the concrete slab of the school playground followed later by Mariana with her mother and brother doing a choreographed dance on the lush countryside as the trio collect chestnuts; children learning about how beans grow in cups for a school project and then later a farmer planting beans directly into the soil. One short sequence of photographic portraitures reminded me of Hu Wei’s fabulous Butter Lamp. It’s all very lovely stuff. Heartwarming without being sentimental. Just not quite the whole that its production suggests it had time to form.

Gods of Stone was preceded at the Sydney Film Festival by a short film: Andrew Norman Wilson’s Silvesterchlausen. They made a fine pair together, with Wilson’s 12-minute opener feeling like the sort of wonderfully fleeting moment that Gods of Stone might have thrown into its early passages. The short tells of a rural tradition for the men of Switzerland that takes place on New Year’s Eve where they dress up in elaborate costumes and masks (that kind of look like the killers in The Strangers or Happy Death Day!) with fantastical headdresses and proceed to sing and dance and play music. It doesn’t feel the need to explain this very peculiar event too much, nor need it have. Like Gods of Stone, it is primarily soundtracked by the sounds of rural life although this is 100% more yodelling than Castiñeiras’ feature. Do with that as you wish.

If you would like to support documentary and non-fiction film criticism, please consider donating by clicking the above link. Any help allows me to continue to do this, supports independent writing that is free of Artificial Intelligence, and is done purely for the love of it.