Life After (dir. Reid Davenport)

Life After is the sophomore feature from Reid Davenport. He is a filmmaker whose first feature, I Didn’t See You There, took a novel approach to observing how somebody who is not able bodied navigates the world. Told largely through a rather simply first-person device of attaching a camera to his motorised wheelchair, it found wit where too often before there had been just stony-faced, well-meaning academia. I was a big fan of it. Whereas I Didn’t See You There was, in its way, trying to illuminate Davenport’s own experiences, Life After seeks to broaden the discussion of the issue of assisted dying to more consciously focus on those who are disabled.

This narrative grows out of Life After’s opening passages, which discuss Elizabeth Bouvia, who at 26 years of age in 1983 decided to end her life through medically assisted starvation in a California hospital. Bouvia and her decision was national news, perhaps most prominently by “Creepy Mike Wallace” (Davenport’s own comical phrasing) looming over her bed in interviews, news television and talk-back radio. A lot of talk of “quality of life” gets thrown around by able-bodied people using (and this is my interpretation) religion in much the same way they did and still do about abortion. They think it’s wrong for somebody to want this, yet likely don’t want to help pay to give disabled people the sort of “quality of life” they deserve.

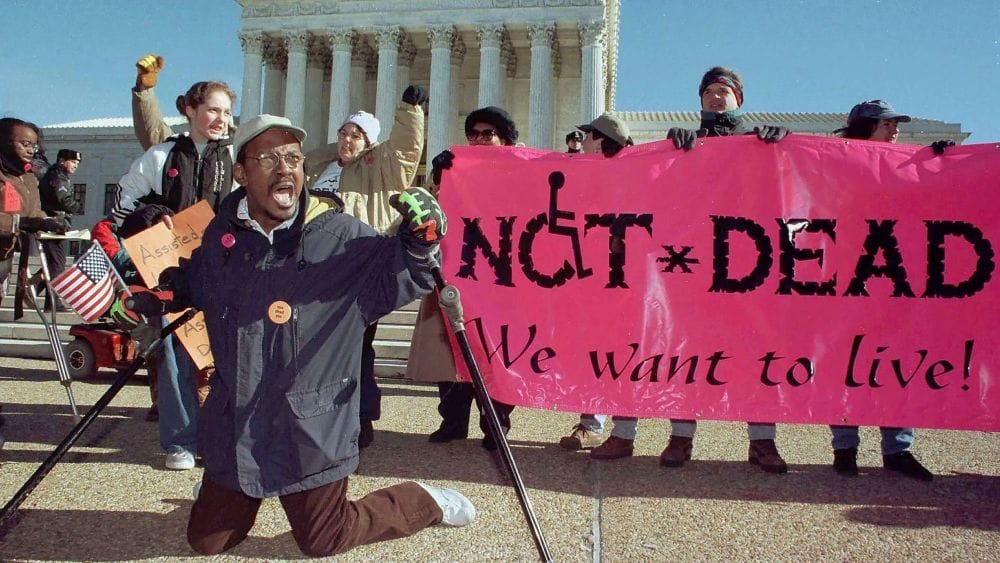

Already, just writing this, I feel like the film has very deliberately sought to fire its viewers up. How could it not? But where you might think Davenport’s film is going in one direction, it actually goes in another. As if to underline the need for the film at all, I suppose. Life After asks a lot of its audience. It ought to. Support for assisted dying has come a long way, and many think it is something of a no brainer should somebody choose to do so. It is therefore perhaps easy to recoil from its message. For a viewer to have their convictions and need nobody to question it. But when you have the United States saying people with disabilities “should just die”, maybe now the exact right time to look at the moral issues around legalised assisted dying in its current form, however (like death in general) uncomfortable it may feel.

Should Davenport even need to show the other side? Plenty of documentaries on the so called ‘right’ side of an argument do not. Who’s to say which side is the right and which is the wrong. If there are sides at all!

Davenport is using the story of Elizabeth Bouvia to make a serious, politically-fuelled documentary. It just so happens it might not be the message many expect. Like abortion or civil rights or same-sex marriage, a lot of people will come to Life After with very firm opinions on its subject. I would say that I still do after watching it and that I disagree with some of what Davenport does here. But that’s part of what makes the film so thorny. Is it just my opinion on the matter clouding my viewing of the film, or is the film doing things that don’t work. Perhaps it’s both.

Davenport puts a lot of focus on the MAID (Medical Assistance in Dying) legislation in Canada but also covers how various states across America have dealt with the issue of assisted dying, also. From what we see, some of the concern that Davenport and others featured here have is warranted. But I couldn’t help but notice there was a lot of so called “advocates” speaking. And any viewer—or filmmaker for that matter—should know better than to put too much stock into people who get paid to change the opinion of politicians. The less said about the politicians themselves, the better. The film doesn’t seem to want to question the motives of some of the people who appear on screen, often labelled as “advocates" and it impacts the film to rely on them talking like they’re television opinion peddlers. It was my biggest issue with the movie.

And furthermore, does Davenport's film, in attempting to raise concerns about how the medical field is pushing death on disabled people actually just end up infantilising those same people in some way? Or diminish their own feelings in suggesting they're potentially all being manipulated? We hear a lot about people who don’t want to die but suggest they have no other option (for example, in one case it's financial), but nothing from those who, like Bouvia, seem defiant in their wishes to end their lives (in Bouvia’s case, at least she was for the period she was in the public eye). In one striking scene, Davenport fills out the online form to apply for MAID and passes “with flying colours”, which suggests the safeguards are likely far too lenient. It upsets him, as it probably should. But are there others for whom that ease would come as a tonic from a labyrinthine world of bureaucracy? Is bureaucracy the quality of life in question for these people? Is bureacracy a reason to end one's life? Should Davenport even need to show the other side? Plenty of documentaries on the so called ‘right’ side of an argument do not. Who’s to say which side is the right and which is the wrong. If there are sides at all!

Bouvia’s story unfolds throughout with the help of her sisters and there are conflicting reports on what ultimately were her wishes while she was alive and out of the spotlight. I guess it would have been easier for Davenport to have just made a film about her and throw some politics for shading in there. I am sure it would have been more successful and won awards I’m thankful in a way that he didn’t, even if I still can’t entirely get behind what he did produce.

The final words that we hear from Bouvia and they are the film's most poignant moment. Spoken by her sister and overlaid with images of Elizabeth from her life, they speak to the heart of the issue that I think Davenport and the majority of his interview subjects are trying to say. That governments and big prophet-run hospitals will have a financial gain in the premature voluntary deaths of so many people, disabled or otherwise. That it will be in their best interests to do so. And that disabled people can foresee their bodies as the front lines in a society that has proven time and time again that it doesn't really think all that much of people with a disability. A society that doesn’t really want these people to have the "quality of life" they keep speaking about because to do so would be to admit that they either directly or indirectly make life extremely hard for disabled people at just about turn. And who am I to not recognise that fear. I can only hope I've interpreted it correctly, because otherwise Davenport doesn't actually see any virtue in assisted dying and I don't choose to do so.

It's a shame we never got to hear those words spoken by Bouvia herself. What a shame that we had no filmmakers like Davenport to even consider doing so while she was still alive. Just "creepy Mike Wallace" and the sensationalism of mainstream news.

If you would like to support documentary and non-fiction film criticism, please consider donating by clicking the above link. Any help allows me to continue to do this, supports independent writing that is free of Artificial Intelligence, and is done purely for the love of it.