Apocalypse in the Tropics (dir. Petra Costa)

Jesus behind every door. A gun in every home. No land for indigenous people and no reparations. These are just some of the promises made by Jair Bolsonaro in his campaign for President in Brazil. Coupled with the blatantly violent rhetoric and threats against left-wing opponents and the disregard for any humanity that doesn’t align with their own fundamentalist, fascistic and uber-capitalist way of governing, and it’s really not that hard to see where they got the inspiration. The implication is MAGA, which isn’t entirely wrong. Certainly, there are specific parts of what happened in Brazil that were directly lifted from what came in America's recent history. They saw what worked in the United States and just copied it. But Brazil (and the US for that matter!) is just the latest in a long line of nations to be corrupted by this sort of cult-like authoritarianism that promises the world to the disenfranchised and delivers only for those within the inner sanctum of its brutish dictatorial figurehead.

As detailed in Petra Costa’s typically sobering documentary, Apocalypse in the Tropics, Brazil has escalated from 5 to 30% of its population identifying as some sort of fundamentalist Christianity. The fastest religious shift in history. If you have been paying attention then you are probably aware that, much like in the United States, Brazil too had a citizen’s uprising, better known as a right-wing insurrection, following an election result that did not go the way its incumbent, Bolsonaro, had wanted, expected, or (and this is the important part) promised his faithful. Anything that went against him and his hard-right movement was a sham. Fake news, if you will. We are told that the first step in any attempt to kill democracy is to call into doubt the very mechanism of voting. It’s wrong, it’s flawed, it’s corrupt and it simply shouldn’t be believed. Any dictatorial manual will tell you that. Unfortunately for Brazil, it was followed to a tee, four years almost to the day after the same thing occurred in Washington DC.

Costa gets great mileage out of its repeated use of the National Congress Palace in Brasilia. With its striking architecture full of symbolic shapes and lines, and the history that we know has unfolded there, Costa’s film is always visually arresting. Her own sombre-toned narration likewise once again imparts upon the viewer a certain sense of unreal reality.

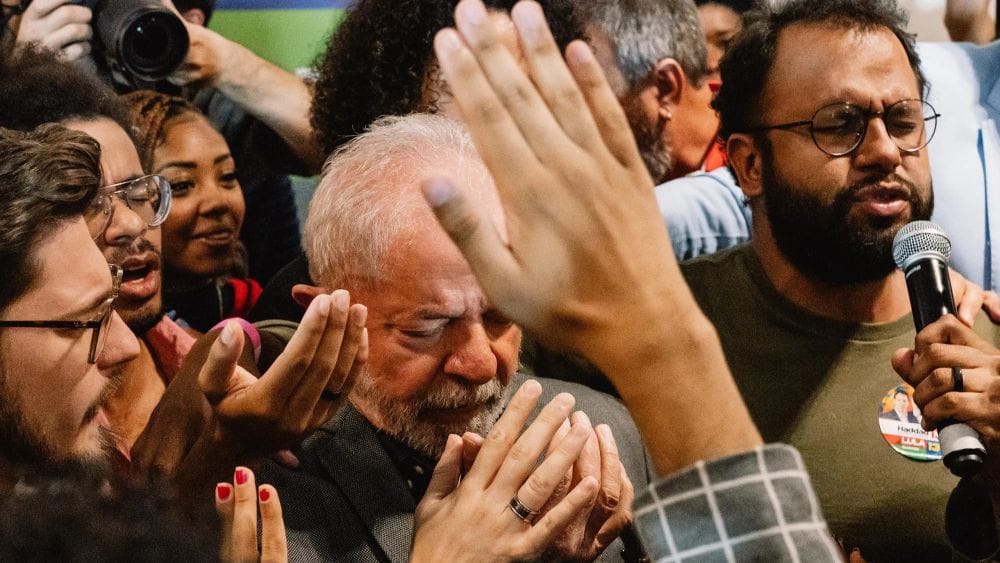

Costa’s film doesn’t so much chart that story (although it’s a fascinating one and it does serve as Tropics’ damning climax) nor the unapologetic approach of its response (at least from the outside; very different to America’s). Rather, she is more interested in what lead her home country to that point. As she had so excellently shown in 2019’s Oscar-nominated The Edge of Democracy, this sort of political unrest is (sadly) hardly new. That film partly documented the rise and fall of Lula da Silva (and the rise of Bolsonaro) who yet again appears in Apocalypse in the Tropics as the saviour (to a point) of the country’s descent into authoritarianism. I have not rewatched that film, but I have no doubt they would make a really fascinating double feature that in some ways recalls Patricio Guzmán’s The Battle of Chile as a sort of multi-part definitive chronical of one incredible period in its filmmaker’s home country’s history. This particular film isn’t quite as good as its predecessor, nor Guzmán’s trilogy, but it struck me as something of an apt comparison.

Again like that earlier film, Costa gets great mileage out of its repeated use of the National Congress Palace in Brasilia. With its striking architecture full of symbolic shapes and lines, and the history that we know has unfolded there, Costa’s film is always visually arresting. Her own sombre-toned narration likewise once again imparts upon the viewer a certain sense of unreal reality. This did happen and whereas I feel some documentarians aren’t suited to being the cinematic voice of their own narrative, Costa (although not for everyone, definitely) gives this story a sad weight that cannot be avoided. Even if, at times, it does become a bit too on-the-nose.

The ace up this movie’s sleeve is the remarkable access that Costa and her team have to Silas Malafaia. He is an evangelical preacher who is considered something of an architect of Bolsonaro’s stratospheric rise to power with his own mission to cleanse Brazil from the claws of evil. His work to sway those large swathes of the countryside—towns and villages that may not have a hospital or paved roads do, however, all have an evangelical church—clearly works, although even he thinks, by film’s end, that his friend and political ally is something of a coward. Costa chart’s Malafaia's own rise amid the aforementioned religious shift, spearheaded by an American pastor and amplified by societal grievances towards the elevation of queer people and environmental protections and the escalation of poverty.

One bit that really stuck out to be was a scene of on-the-street jubilation from a woman, celebrating the political win of her hero, Bolsonaro. “The dictatorship is back!” she shouts directly at the camera. They want this. They want a dictator if it means those they don’t agree with get taught a ‘lesson’. Again, we have seen this many times including just last year with Donald Trump. One of the great things about Apocalypse in the Tropics is that it is clear-eyed about the problems that its filmmaker’s homeland faces. It’s not new or original. It plays the story of Brazil very directly. There’s no doubt a hell of a lot more to the story and maybe there’s another film’s story to tell in a trilogy capping feature. But this is an incisive look at one country’s perilous descent into dangerous extremism that has the wisdom to know that nothing will ever be safe as long as inequalities continue to manifest and expand like a virus.

If you would like to support documentary and non-fiction film criticism, please consider donating by clicking the above link. Any help allows me to continue to do this, supports independent writing that is free of Artificial Intelligence, and is done purely for the love of it.